The current covid-19 crisis highlights the fragility and non-durability of contemporary social systems, but also the consequences of considering nature as external to ourselves. Nevertheless, the pandemic has also been a source of inspiration and collective creativity. Confronted with the urgent challenge of addressing some of the underlying social-structural problems related to inequality, renewed debates and bold proposals have emerged towards the realization of a more resilient, sustainable, and fair society. A key platform of debate is the UN’s AI for Good Global (AIGG) series which is a leading and inclusive action-oriented summit on artificial intelligence (AI) [1]. Organized every year in Geneva by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in partnership with over 35 other UN agencies, its goal is to identify the practical applications of AI and consider how they may be scaled up to address pressing global issues. This year the AIGG has identified three fields of action: gender, food and pandemics [2].

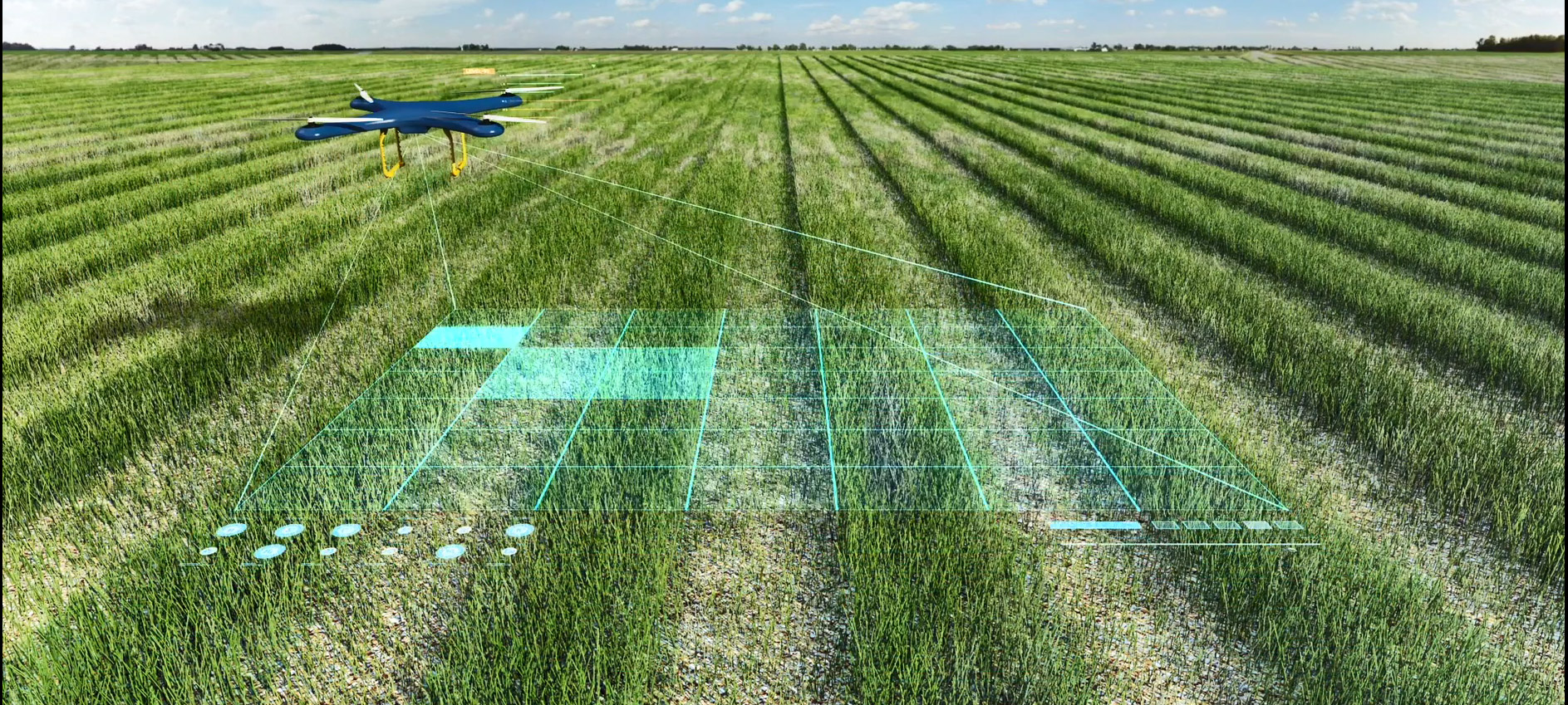

The 2020 breakthrough days event aimed to advance projects in each of these fields in a bid to help meet the UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDGs) [3]. Specifically, the conference entitled “Food revolution” conducted by the President and CEO of the B Corp Danone Emmanuel Faber, focused on the central role that firms must play in the transition to more sustainable and resilient agricultural models. Faber affirmed that he is committed to a business model that supports a food revolution based on alternative agricultural practices, to which AI could benefit. He explained that using the information captured by drones, it is possible to measure the carbon footprint of certain agricultural activities and gather data about the growth of trees, crops, and mangroves which are some of the most effective carbon sinks [5]. AI support in agriculture is thus critical in the fight against inequality and climate change, particularly because of its emphasis on the protection of biodiversity.

In any discussion about the worldwide food system, it should be kept in mind that one-third of current farmland is degraded, up to 75 percent of crop genetic diversity has been lost and 22 percent of animal species are at risk. Furthermore, over half of fish stocks are fully exploited and, in the last decade alone, some 13 million hectares of forests a year have been converted into other land uses [6]. It could be argued that these trends are the result of the predominant socio-economic system, which, in seeking to achieve profit maximization is threatening the stability of the very ecosystems on which they depend for resources. Indeed, modern farming is not only contributing directly to climate change through the release of methane and nitrous oxide, two powerful greenhouse gases, but it drives a large percentage of tropical deforestation. With regards to global development, it reinforces the unequal practices across and between countries, as much of the land in the global South is used to feed mouths in Europe and North America [7]. For its industrial practices, the classic agricultural model has generated excessive dependence on limited supply chains, weakened producer-consumer relationships and damaged the environment [8]. It will not be possible to achieve agriculturally sustainable rural development or food security if efforts to this end ignore the role of women in food production. The UN conference (2011) about the vital role of women in agriculture, showed that eliminating the gap between men and women in access to agricultural resources would raise yields on women’s farms by 20-30 per cent and increase agricultural production in developing countries by 2.5-4 per cent. This in turn would reduce the number of undernourished people by 12-17 percent or 100-150 million people [8]. Mobilizing women in the developing world to increase yields is an old solution to an old problem; now let’s turn to the new and potentially equally as effective solution: AI.

In recent years, interest in AI and its role in food security has increased, bringing a range of hopeful possibilities to the table [9]. AI functions through a combination of algorithms whose purpose is to perform actions in response to predetermined contexts, as any human being could do. In its most rudimentary form, the power of AI resides in its ability to process data, with connectivity being a key ingredient [10]. In order for it to prove a realistic solution in the Global South, where 50% of the world’s food production is generated, high-tech infrastructures such as optical fiber, broadband and satellite receivers need to be upgraded ,to record, store and share climate indexes, weather forecasts and market price dynamics,. Educating the local population to make use of such data will also be critical in the integration of AI and may also help to emancipate rural farmers from wider political and economic restrictions. The use of AI in developing countries is not however restricted to agronomic resource management and livestock monitoring but could be used in a variety of other contexts including tracking a disease outbreak or recording damage after a natural disaster [11]. AI also has a role to play when it comes to consumers, with the potential of educating them about the best food options for their health or for environmental sustainability.

There are dangers to this approach however, with the consumer potentially being deceived by misconceptions through blindly trusting the AI without critically engaging with the information provided [12]. At their worst, AI technologies could reinforce a dysfunctional system that excludes the most vulnerable members of society, having negative effects on food security, equity, and social justice.

By reinforcing existing social biases, AI systems can potentially marginalize some groups including women, ethnic minorities, or family farmers. For this reason, governments and legislators must work hand in hand in order to develop a system that works for everybody. International governance mechanisms and processes must support sustainable growth (and the equitable sharing of benefits) in all agriculture sectors, protecting natural resources and discouraging collateral damage [13].

The possibilities of AI are endless and clear, but the risks tend to be more hidden. This gives rise to a central question: How is it possible to ensure good governance of data collected by AI, which allows individuals to be empowered and not enslaved? First of all, AI must be considered as a common good to ensure an ethical and democratic use of the data collected among all the inhabitants in the world. Therefore, it should be developed using a bottom-up and integrated approach, where all the actors in the production, distribution and consumption cycle can contribute and benefit. The food revolution then requires the collective re-appropriation of issues related to safe, diverse, nutritious, and affordable food- an idea known as food sovereignty [14]. Such a transformation should integrate all political domains, demanding structural modifications of society and the economy. Thus, the realization of the sustainable development goals proposed by the UN depends on the commitment of the stakeholders in the implementation of these objectives. For the general population, it is important to raise the question of the democratization of AI, the socio-technical blocking mechanisms, and data transparency.

Laisser un commentaire

Vous devez vous connecter pour publier un commentaire.