On Saturday 4 December, the island of Java (Indonesia) experienced a phenomenal volcanic eruption, killing at least 14 people and injuring another 50. Over the past two years, the Semeru volcano has already erupted four times [1]. While a dozen people remain missing, thousands of Indonesians are now without shelter, forced to sleep in mosques, schools, or community halls [2]. Two weeks later, on Friday 17 December, Super Typhoon Rai slammed into the Philippines (one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable nations, hit by nearly 20 tropical storms or typhoons each year), causing more than 375 deaths, and forcing at least 332,000 people to evacuate their homes and thousands to flee [3]. These people, who are now seeking safety somewhere else in their own country, are commonly referred to as IDPs: Internally Displaced People. Unlike refugees, IDPs don’t flee from their country but within it, in search of security. IDPs are also supposed to be under their own government protection. However, as climate disasters are dramatically increasing, so is the number of internally displaced people, as well as the account of climate refugees all around the world. As the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) explains, “many are living in climate ‘hotspots’, where they typically lack the resources to adapt to an increasingly hostile environment” [4]. And the correlation between those responsible for global warming, and its victims, seems more negative than ever.

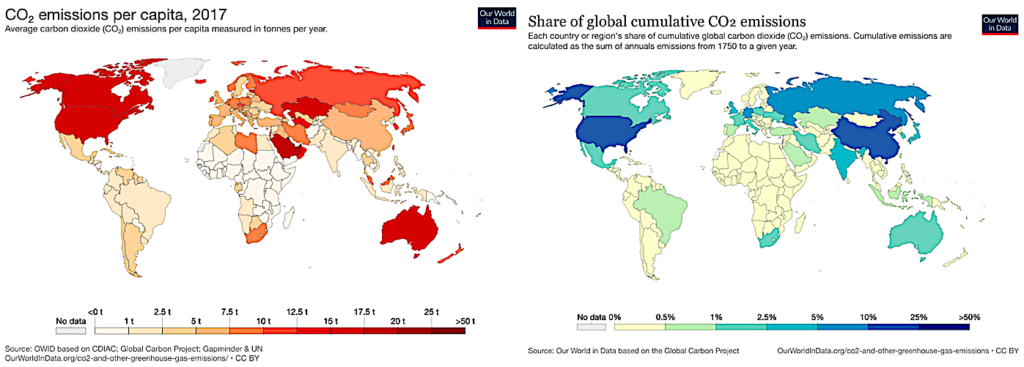

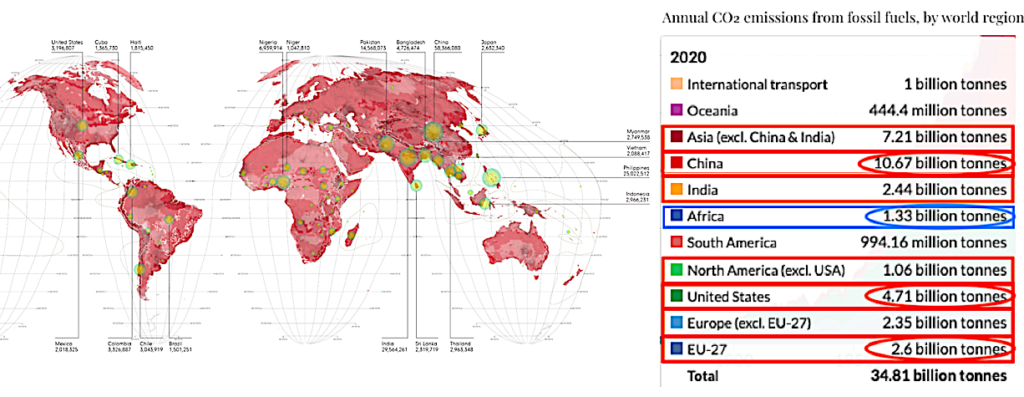

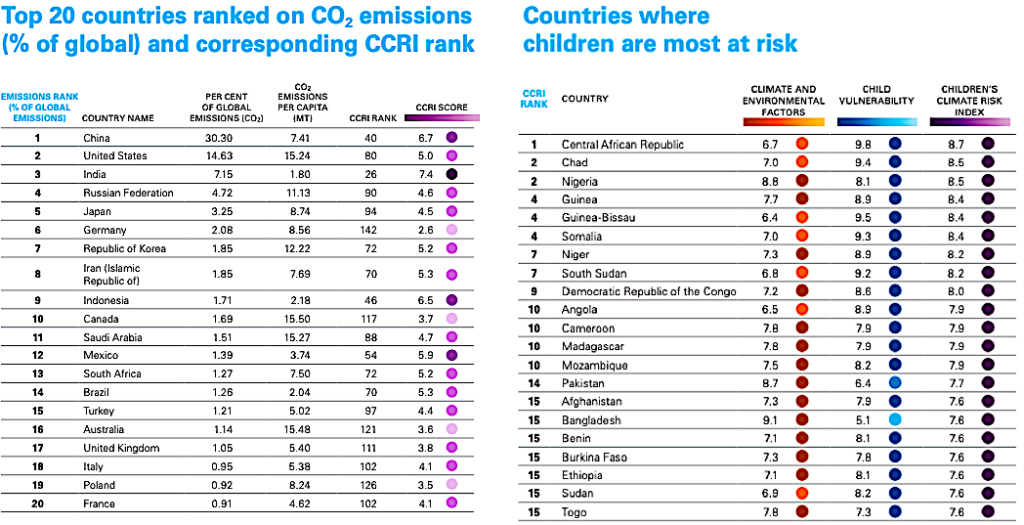

Indeed, while developed countries are most to blame for the climate decline (see Maps 1 & 2), they also conveniently have the lowest amount of environmental IDPs (see Map 3). According to UNICEF, the 10 highest-risk countries in the world only emit 0.55% of global emissions [5]. Still, many critics argue that Africa is just as much at fault for environmental issues because of its “overpopulation”. Nonetheless, these accusations remain factually void. As a matter of fact, despite being the second most populous continent (as well as the second-largest continent in the world), Africa is actually one of the least densely populated (number of inhabitants/km2) continents in the world. With only 40.45 inhabitants per km2, Africa’s “overpopulation” is far behind that of Asia (99.51 inhabitants/km2), Europe (74.35 inhabitants/km2) or the Americas (44.73 inhabitants/km2) [6]. Besides, in 2020, the entire continent’s CO2 emissions from fossil fuels accounted for only one tenth of China’s, one fourth of the United States’, and half of Europe’s (see Table 1).

Map 2. Share of global cumulative CO2 emissions in 2020 – Our World in Data

Table 1. Annual CO2 emissions from fossil fuels, by world region – Our World in Data

(blue and red emphasis by myself)

Notwithstanding these burning facts, countries like South Sudan (which is only accountable for 0.004% of the world’s gas emissions [5]), have experienced record floods that have forcibly displaced hundreds of thousands of people. The Independent even recently titled: “Flooding in South Sudan threatens a nation on the edge” [7], after the United Nations evidently accused climate change for the fact that the state has experienced “extreme flooding” for the past three years [8]. According to Adesh Tripathee, Regional Head of Disaster and Climate Crisis for Sub-Saharan Africa at the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), more than 700,000 people are currently affected by floods, as he alerted about “a critical humanitarian situation” [8]. The World Meteorological Organization on the other hand warned of “increasing such climate shocks to come across much of Africa, the continent that contributes the least to global warming but will suffer from it most” [8]. The continent also faces higher rises in temperature than the rest of the globe [9].

Image 2. South Sudan, 2007 – United Nations Photo

In South Sudan, many of these displaced people who have moved multiple times inside their own boarders now wish to leave the country in order to find safety somewhere else. As Climate Refugee also explains, “climate change can serve as a ‘threat multiplier’ by exacerbating existing risks and creating new ones” [10]. John Payai Manyok, the country’s Deputy Director for Climate Change confirmed the latter by deploring: “This [climate change] is becoming a crisis. It’s leading to food insecurity, [and] to more conflict within the area because people are competing for the little resources that are available” [9]. In a recent interview with Clarissa Ward (CNN), Sudanese Nereka, mother of a 5-month-old baby, shared: “Of course I’m worried about my children. That’s why we keep moving” [9]. James Ling, another Sudanese citizen, also pitied: “Since the conflict erupted, we have never had a rest. We have been constantly running, displaced. Our children have had no relief from the dangers” [9].

The top 20 countries in the world responsible for CO2 emissions are mostly European, Asian and American. Yet, the nations whose children are most at risk from the climate crisis are almost all African. The Central African Republic is also listed as the country where its children are most at risk, despite being the lowest emitting country in the world, with only 0.001% of global emissions [5].

Considering that the Earth is already 1.2 degree Celsius warmer than it was before the 19th century industrialization [9], are governments – and by extension the international community – truly preparing, not only for the prospects that are ahead, but for those that we face right now?

In anticipation of the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26), the HCR urged all state-parties to not only “combat the growing and disproportionate impacts of the climate emergency on the most vulnerable countries and communities — in particular those displaced and their hosts”, but to also “support vulnerable countries and communities in their efforts to rapidly scale up prevention and preparedness measures to avert, minimize and address displacement” [4]. Nevertheless, the G20 – which is primarily responsible for the environmental crisis – continues to agree on changes for a foreseeable (if not distant) future but refuses to see and address the pressing truth: that disaster displacements are a living reality right now, for millions of people across the world.

In addition, international law remains flawed when it comes to protecting displaced persons due to environmental factors, since no real “environmental refugee” status exists. As explained by António Guterres, UN Secretary-General and former UN High Commissioner for Refugees, “climate change [is] now found to be the key factor accelerating all other drivers of forced displacement. Most of the people affected will remain in their own countries. They will be internally displaced. But if they cross a border, they will not be considered refugees. These persons are not truly migrants [either], in the sense that they did not move voluntarily” [10]. Given that environmentally forcibly displaced individuals are not covered by the refugee protection regime, they therefore find themselves lost in a dangerous legal void, that the international community has yet to fill…

Laisser un commentaire

Vous devez vous connecter pour publier un commentaire.