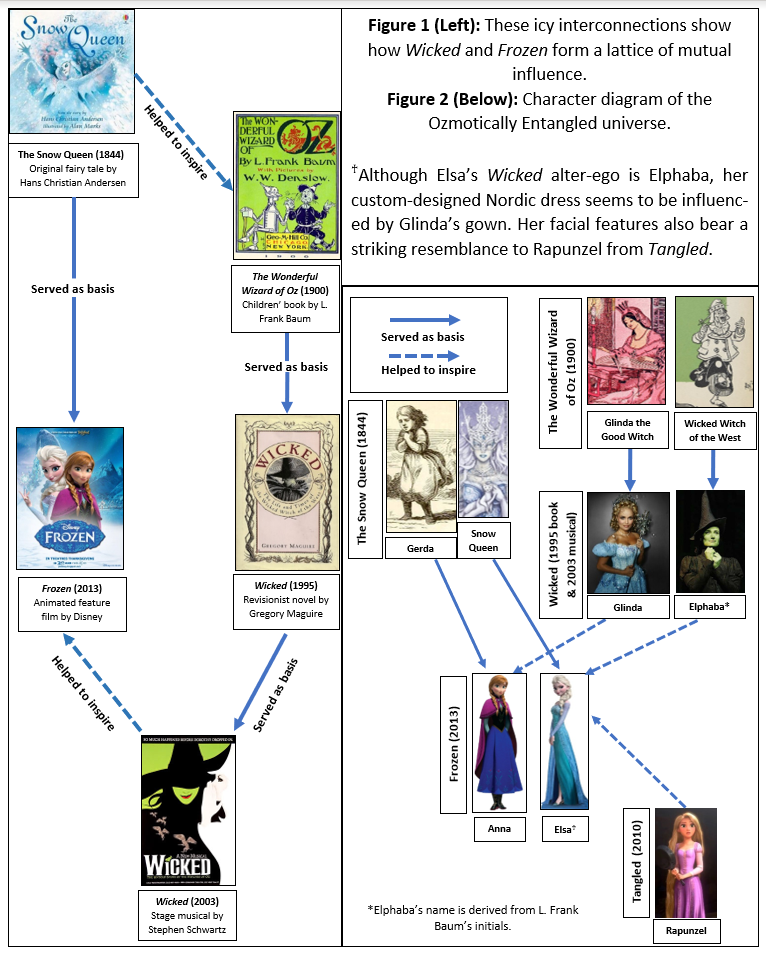

The Snow Queen helped inspire The Wizard of Oz1. Andersen’s famous fairy tale features a fantasy world of witches, wizardry, and winged demons2, which form the bread and butter of Baum’s best-selling book. Each story’s principal protagonist is a gleeful girl who gets herself tortuously tangled up in a dream-like domain and must surmount a sinister sorceress to head home. Both paint a paradigmatic picture of good and evil. In Andersen’s account Gerda’s generous love is enough to eradicate the malevolent mid-winter monarch, while in Baum’s book good and evil are personified by two people: Glinda the Good and the Wicked Witch of the West. The former is presented as brilliant, beautiful, and benevolent, whilst the latter is unambiguously hideous and hostile.

Gregory Maguire, however, turns all this on its head. In his 1995 novel Wicked, he reimagines Oz’s enchantresses as endearing yet multifaceted women, ill-suited to the labels they are lumbered with3. Glinda is the spoilt rich girl, more preoccupied with popularity than magnanimity, while Elphaba is the diffident do-gooder, demonised for her sickly appearance and mysterious powers. Both girls must grapple with the paradox of how people perceive them, even as they evolve into ever more complex creatures. The intimate interplay between the two is expertly transposed from the book into the musical as the two headstrong heroines combine for a scintillating showpiece songfest. Glinda and Elphaba move from antagonism to affection and back again as scriptwriter Stephen Schulz applies the traditional tropes of heterosexual romance to the forthrightness of female friendship. The series of duets between the pair is reminiscent of Rodgers and Hammerstein classics where the leading lady bickers with her suitor (Think Oklahoma! and Carousel). By putting a queer spin on it, Schulz satires the stranglehold of straight storytelling, making us wonder why it continues to dominate the decking boards of Broadway4.

Borrowing from the Wicked spell book, Frozen’ s creators cast much the same trick. By making Anna and Elsa siblings with polar-opposite personalities, Disney delicately depicts the subtleties of sisterhood in riveting and relatable fashion. Just like their Oz-tensible counterparts, Anna and Elsa’s relationship moves from fiery to frosty and back again through a medley of melody, mayhem, and misadventure. Close as children, the two grow apart as Elsa’s parents condemn her to conceal a supernatural secret. Left out in the cold following their death, she ice-solates Anna, putting a freeze on her ambitions to marry. Unlike in Wicked, the girls ultimately find a way to artic-ulate their feelings as Anna melts Elsa’s frozen heart to thaw the winter of discontent.

Elsa, after all, had been eccentric, elusive, and enigmatic exactly like Elphaba. Indeed, the two characters take much the same arc, as both are born with powers they did not choose, only to be relentlessly reviled for revealing them. Hell, they were even played by the same actress. Disney desperately desired to recreate the wonder of Wicked and knew Miss Menzel could sprinkle some supernatural stardust over their Snow Queen. Having deftly defied gravity on Broadway, there was little doubt she could let it go in Hollywood. Her interpretation of both signature songs is simply sensational and effortlessly epitomises Elsa and Elphaba’s ecstasy at finally finding freedom.

Idina Menzel (Elphaba) and Kristin Chenoweth (Glinda) perform Wicked’s defining duet, Defying Gravity.

Let it Go was written before the plot of Frozen was firmed up, convincing the creators to craft Elsa’s story as the escaping empress. This reflected the organic production process that Disney deployed, with the characters and music mutually influencing each other5.

It also helped decipher a dilemma which had dogged development since 1937: how to adapt Anderson’s archaic characters to the silver screen6. Production had been put on ice on numerous occasions amid brain freeze on how to make them both narratively and graphically relatable. Weaving in Wicked’s wit worked wonders for the writers, while the graphic designers drew on technology tested for Tangled.

This adaption of the maiden-in-the-tower tale had relied on a hybrid of hand-drawn and computer-generated imagery. Long a fringe technology, it allowed the animators to bring Rapunzel’s lovely long locks to life. Its shear versatility was then applied to Frozen’s windswept winter wonderland and carefully choreographed characters7. It provided detail so rich that a costume stylist could be brought in to design Elsa’s dresses – a first for an animated film8 (see note below figure description).

Frozen followed Tangled in several other aspects too- most controversially a name change to market the movies as more gender neutral. In effect, Disney ditched the traditional titles for fear that boys would balk at them9. This is an ignominious irony given how they otherwise gloriously grapple with girly liberation.

Indeed, the treatment of this topic is what most unites the productions we’ve pondered. Drawing on a heavy history of mutual influence, both Frozen and Wicked unabashedly uncover the unique undercurrents of being a woman in a world where they are told to conceal not feel. By showing an audience of all ages how to embrace their true identity, they take this harmful narrative and let it go. That may not be enough for every girl to defy gravity. But, for the first time in forever, at least they’ve got a chance.

Laisser un commentaire

Vous devez vous connecter pour publier un commentaire.