“Spaniards… Franco is dead”. 20th November 1975. The long-awaited announcement was finally made by PM Carlos Arias Navarro. Just two days after Juan Carlos de Borbón succeeded Francisco Franco in power following the dictator’s wishes. Today, Felipe VI, Juan Carlos de Borbón’s son, remains the Head of the Spanish State 52 years later. Up until now, no one except for dictator Francisco Franco has elected the monarchy as the form of government in the country.

In 1977, the first democratic Parliament signed the Amnesty Law for all the political prisoners of the dictatorship. The law also guaranteed the impunity for those who participated in crimes during the civil war and the dictatorship. But the Amnesty Law was the key towards transition to democracy : in the late 70’s, both the regime’s supporters and the opponents were exhausted of fighting and suffering. However, the Amnesty Law has never been revised; the Spanish Parliament denied a petition from left-wing parties asking for its modification on 20 March. Both the civil war and the dictatorship continue to be a dark and problematic period in the history of Spain. The Amnesty Law has become a dead-end for many victims seeking reparation and justice, as well as an insurmountable obstacle to fully understand contemporary history and politics of Spain.

“The Silence of the Others” in FIFDH 2018

Indeed, there were many opponents to the dictatorship, and still there are. Almudena Carracedo, a young Spanish film director, is the co-author of “The Silence of Others” whose Swiss Premiere was presented at the FIFDH 2018 – International Film Festival and Human Rights Forum – where it was awarded with the Special Mention of the Jury for Creative Documentary. The projection of this moving film was followed by a fruitful debate involving co-director Almudena Carracedo, Jose Maria « Chato » Galante, spokesperson for the Platform in support of the Argentina Lawsuit (CEAQUA), Kate Gilmore, United Nations Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights and Maite Parejo Sousa, Vice-President of the Spanish Association for Human Rights. The debate was moderated by Sevane Garibian, professor of transitional justice at the University of Geneva and head of the FNS research project “Right to Truth, Truth through Rights”[1].

“The Silence of The Others” portraits the struggle of those survivors and the evolution of a seemingly never-ending lawsuit, aiming at unburying the past and finally obtaining justice. The story is told in present tense. Its purpose is to inspire new generations to discover its past, a past that has so far been denied to them. The historical judicial dialogue between Argentina and Spain portrayed in the film has given hope to many victims during the long 18 years of a still ongoing process.[2]. As an example of a judicial struggle, we get torn apart by the strong conviction of María Martinez, an elderly lady whose only wish was to be buried with her mother’s remains that were, as many others, interred in a mass grave. María Martínez died before the trial’s resolution; in this fight, time is also an enemy.

Not only do these advocates and civil societies work on filling the gap in history but also on dealing with the Spanish quotidian denial. As Jose María “Chato” explained in the debate, forgiveness is an individual feeling that can by no means be granted by a state. Neither should states require their peoples to forget about a piece of their history. This project intends to reopen the polemic question of the Spanish identity, robbed from half of the population, vanquished by Franco’s propaganda strategies.

The “Valley of the Fallen”, a shameful symbol of an open wound

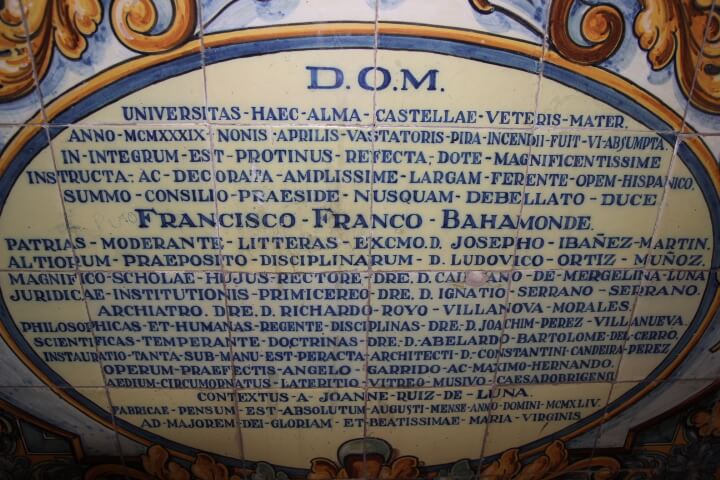

In “Valley of the Fallen”, a Catholic basilica in northern Madrid, dictator Francisco Franco rests in peace. In this memorial, an estimated number of 3,000 anonymous bodies from mass graves are also buried. In the debate that followed “The Silence of the Others”, Jose María, “Chato” said: “Imagine that Hitler was buried in the outskirts of Berlin, in a huge memorial with 4000 or 5000 of his Jewish victims.” A comparison that speaks for itself.

The “Valle de los Caídos”, its original name in Spanish, was strategically built on top of a mountain. Dictator Francisco Franco officially inaugurated the basilica on April 1st, 1959. It is situated next to the biggest tunnel in the region that connects Madrid with northern Spain. Thousands of drivers pass by day after day. Like the Egyptian pyramids, the memorial risks becoming an artistic monument of a past era. Therefore, its appalling connotation would be forgotten. Up until now, no government has had the courage to demolish it, or at least, to start a necessary debate on how to reconsider these national wounds. Today, the “Valle de los Caídos” is a touristic attraction with great views, as well as a terrifying symbol that many people still fear.

In the meantime, the Francisco Franco National Foundation tries to preserve its legacy and safety. But not for much longer. For the first time in history, an exhumation of the soldier’s graves is taking place from 23th April onwards in “Valle de los Caídos”. A group of family victims has won the trial against the Catholic Church, the owners of the basilica, to have the permission to open the graves. Among those who won the trial there are also family members of two “nacionales”, word to refer to those who supported the regime in the past. It is a hopeful sign of how times can finally change.

#8000, towards a change from the grassroots

Tortured people. Political prisoners. Political exiles. Interior exiles. Deportees. Fugados [4]. Condemned to death following a fake trial. Condemned to death without a trial. Deaths in battles, deaths in the streets, deaths in bed. Missing children. Orphans; stolen babies. Deaths in the name of the “defence of the homeland”. Deaths in the name of freedom. Deaths in the name of Francisco Franco. Deaths.

Are these words meaningless? Do they achieve any sort of reparation or justice for the victims? How to tell History? How to simply tell? Shall we tell our past, or start on a clean page? With which aim are we telling our past? Does History somehow redeem the past? And Law?

In fact, it is difficult not to reproduce the same discourse of horror and fear repeatedly. However, at the end of the debate that followed “The Silence of the Others” film projection, Kate Gilmore, UN Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights, suggested: “Justice can be achieved in different ways. Susan Sontag said that the veritable pornography is to look at suffering and do nothing. (…) I believe in the power of music and literature, in composition and pen, in the power of narratives to achieve reparation.”

In such a context, film director Almudena Carracedo added: “when work finishes, it is when work really starts.” Her aim is to bring the film to every one of the 8000 municipalities in Spain[3]. To finally start a dialogue; to never forget.

A short list on further readings and films:

. Novels and essays (all titles are available at the library; though most of them have not been translated yet):

Cercas, Javier, Soldiers of Salamis, New York: Bloomsbury, 2001.

Delibes, Miguel, Los santos inocentes, Barcelona: Planeta, 1981.

Gibson, Ian, Cela, El hombre que quiso ganar, Madrid: Suma de Letras, 2004.

Laforet, Carmen, Nada, Barcelona: Destino, 1987 (Translated into English, though only available in Spanish at the library).

Méndez, Alberto, Los girasoles ciegos, Barcelona: Anagrama, 2008.

Preston, Paul, The Triumph of Democracy in Spain, London: Methuen, 1986.

. Films on the dictatorship:

Erice, Victor, The Spirit of the Beehive, 1973 (A masterpiece).

García Berlanga, Luis, Plácido,

The executioner, 1963.

Welcome Mr. Marshall!, 1953. (Three excellent portrays of society during the dictatorship).

Martín Patiño, Basilio, Canciones para después de una guerra, 1976. (an audacious documentary filmed shortly after Francisco Franco’s death).

. Films on the transition to democracy:

Chavarri, Jaime, El desencanto, 1976. (a documentary on literature).

Bardem, Juan Antonio, Siete días de enero, 1979 (on the Amnesty Law and its historical context).

Almodóvar, Pedro, Pepi, Luci, Bom, 1980.

Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, 1988 (because after all…. there is always room for humour). [5]

Laisser un commentaire

Vous devez vous connecter pour publier un commentaire.